Successful Public Education Campaigns—It’s Not About What You Spend, It’s About What You Say

The allure of a public education campaign is undeniable. Board members love the idea and may think that these campaigns are the answer to raising the public profile of their profession. Even staff often are drawn to the idea, because public education campaigns can be a lot of fun and a welcome change from business as usual. And consultants and marketing communications firms really love association public education campaigns because we can work with you on these initiatives.

That said, successful public education campaigns share some common elements. And you might be surprised to know that one of them is not necessarily how much you spend. What follows is a discussion of what you need to do and know before you embark on a public education campaign if you hope to succeed.

Step One: Clearly Articulate the Goal of Your Campaign

This is not as easy question to answer as you may think. In fact, if you get a group together (internal staff and/or board members) you will likely find that you hear multiple responses. Take the time to reach a consensus. Just as important, make sure the goal is something that others actually care about or at least something will care about once you educate them.

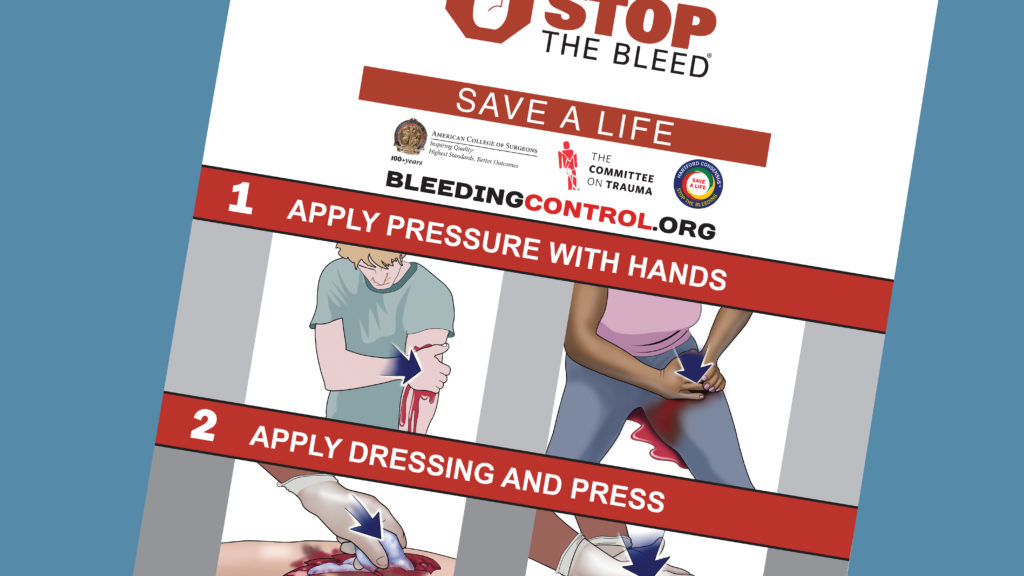

The reality is that public education campaigns that are built around raising the profile of the profession will fail. That should only be seen as a byproduct of doing a public good. As an example, and one that I will refer to throughout this article is the Stop the Bleed® campaign. This Department of Defense program has been embraced and become a major initiative of the American College of Surgeons (ACS). In broad terms, this initiative came about after the Sandy Hook tragedy highlighted the need to teach people—like you and me—to stop life-threatening bleeding—before first responders could arrive. The ACS saw an unmet need and has since become the leading organization in terms of training instructors to stop the bleed and training the public with nearly 60,000 instructors and more than 1 million people trained worldwide.

Certainly, the American College of Surgeons is now known more widely than it was before it began its public outreach with the Stop the Bleed initiative, but that was not its primary intent. The campaign was designed to meet a public need. The goal was clear—to teach the public to be immediate responders.

Step Two: Define Your “Public”

A common mistake that associations make when they launch public education campaigns is that they assume that the “public” means the public at large. The public at large is not only a huge, heterogeneous group, but it is virtually impossible to reach in a cost-effective way unless you have unlimited funds. Take a step back. Is the general public really the group that you are trying to reach? The more precisely that you can define your public, the more effective your campaign will be. As an example, let’s consider a physician specialty organization that is trying to protect its scope of practice, since anyone with M.D. after their name can legally perform a procedure without board certification in that specialty.

Option 1: Launch a public education campaign directed at the general public campaign explaining board certification and why that is important.

Option 2: Launch a public education campaign directed at policymakers explaining board certification and why that is important.

There are two benefits to Option 2. First, Option 1 is not only expensive, but based on what we know about how people choose their physicians, likely ineffective. Board certification is not high on the list factors for physician selection—certainly lower than word-of-mouth and location. Option 2 may or may not be effective, it will depend on additional work. The message must be supported by actual evidence that physicians outside the specialty have compromised patient safety. If so, then the association’s campaign will have teeth. If not, then it is questionable whether the campaign, at the end of the day, is for the public good.

Step 3: Be Creative in Getting Your Message Out (It Doesn’t Have to Be Expensive)

The American College of Surgeons had virtually nothing budgeted when it committed to its Stop the Bleed initiative. Even today, its investment is minimal. Certainly, if your association has a lot to invest, that’s great, but don’t be deterred if your funds are limited. On the other hand, if your cause is worthy, lack of funds should not be a limiting factor.

It stands to reason that the more narrowly you define your “public,” the greater likelihood there is that your message is to reach your intended audience. For example, if your public is the local community getting your message heard is going to be much easier than if you are trying to reach the entire state. Or, if you are trying to reach state legislators, that task will be more achievable and affordable (in most cases) than trying to educate the U.S. Congress.

That isn’t to say that some public education campaigns should be limited in scope and size. For example, the American College of Surgeons set its site on teaching everyone in America how to stop life-threatening bleeding. It recognized that this was a lofty goal, but it also recognized that there was a public health need and that it could not be prioritized based on geography, income, or any socioeconomic factor. The ACS also realized that at the time this initiative became a priority it had not budgeted for a public education campaign of this magnitude.

It is not simply good fortune that despite its financial constraints and hard work of its physician leadership and staff that the ACS Stop the Bleed initiative has trained more than 1 million people in life-saving bleeding control techniques. The success of the ACS’ public education campaign and other successful public education campaigns share some common attributes:

1) They tap into a real public need

As mentioned earlier, and bears mentioning again, the success of any public education campaign depends first and foremost on whether the public you are trying to educate is or can be convinced that your goal is a worthy one. It cannot be self-serving. Self-serving campaigns disguised as public education campaigns ring false and are a waste of time and money. In fact, they probably do more to hurt your association’s image than if you did nothing at all.

2) They are based on realistic expectations

Public education campaigns should be based on realistic expectations or your association (and your board, in particular, is likely to be disappointed). That isn’t to say that you can’t have auspicious goals, for example, a commitment to ending homelessness, but your campaign must then outline a plan that at least shows a pathway for moving in that direction. Platitudes are insufficient.

Another example of what might be considered an unrealistic goal would be one that defies marketplace realities. Considerable research exists, for example, on how people choose their physicians. Topping the list of decision factors are things like word-of-mouth recommendations, recommendations from another trusted physician, and proximity to home. Of lesser importance are things like whether the physician belongs to a professional association. Before you get upset, belonging to a professional association is extremely important for many reasons, including for continuing education, advocacy, networking to name a few.

But let’s say that an association wants to build a public education campaign to educate the public about how its members are the cream of the crop because they belong to the association and as a result when choosing a physician in that specialty, they should choose a member of that association. Based on what research shows that campaign will fall short of expectations or at best, take a long time and require a huge expenditure of resources to move the needle. (As an aside, associations that have “Find a member” locator tools on their websites that have been optimized can accomplish this goal of driving the public to the association’s member in greater numbers way more cost-effectively.)

3) They attract collaborators and supporters

Worthy causes are attractive to like-minded organizations and companies. It is worth seeking out potential collaborators if you believe they can add strength and credibility to your efforts as well as funding sources whether it be foundations or private-sector entities. The ACS has been fortunate to receive both in-kind donations and private funding for its Stop the Bleed initiative. In addition, logos for a number of government entities, who participated in the Hartford Consensus, which was the catalyst for Stop the Bleed, appear on the Stop the Bleed website (www.stopthebleed.org) , give additional gravitas to the effort.

4) They are multi-dimensional and measurable

This shouldn’t be revelation, because associations already know that a public education campaign is a really just a marketing campaign on steroids. And no marketing campaign is one dimensional. Your marketing mix will obviously depend on who your public is and the complexity of your message. For the ACS, since the public in the larger sense and legislators are its two main target audiences, many different communication vehicles and strategies are used, including twitter (@bleedingcontrol), the website, story pitching to national media, PR newswire, bleeding control training members of the House and Senate and their staff, among others.

The metrics used to gauge success are fairly straightforward. How many instructors are trained each month and how many members of the public are trained each month? Of course, growth in Twitter followers, media mentions, and training on the Hill are easy to quantify too.

5) They are sustainable

I recently spoke with an association executive who shared a link with me showing a portion of her association’s public education campaign. It was fairly impressive. I asked her how things were going and she responded, “Oh, it’s over. Once the agency stopped working with us, that was pretty much it.”

The point here is if you decide to work with an outside firm, you want to make sure that whatever they work with you to create is something that you have the ability to manage once they depart or alternatively that you have the money to keep the firm on board for the duration of the campaign.

Some Final Thoughts

So, should you consider launching a public education campaign? That’s a definite maybe. If you have identified a true need that will resonate with others, then it is worth considering. Don’t let money be a limiting factor. Don’t let unrealistic expectations cloud your focus. Seek out partners who can add credibility to your efforts. Be creative and educate your public on many fronts. Measure and fine-tune your efforts. Educating the public—any public—takes time. Make sure you are committed not for a week, not for a month, but for as long as it takes to make a difference. Good luck!

Tags

Related Articles

Report Reveals Strategies to Overcome Membership Decline

McKinley Advisors’ Membership Reset report provides a roadmap that association leaders can use to refocus...

Member Retention: More Than Just a Number

Learn how the AANA used humor and multichannel marketing to win back lapsed members.

Building Tomorrow: HACIA’s Member Development Initiatives Are Reshaping the Construction Industry

Jacqueline Gomez, Executive Director of the Hispanic American Construction Industry Association (HACIA), describes the crucial...